#1: Mechanics of The Game of Life

#1: Mechanics of The Game of LifeNot having read the Complexificaiton reading last week, I didn’t know that the Schelling’s racial housing preference model was outlined there. Variants on game of life (herein, GOL) models are extremely interesting. The mechanics are barely touched on in the chapter from Casti. The reading is a great overview of the systems but doesn’t serve to differentiate between traditional automata and those which expand on GOL (or substitution systems for that matter).

In GOL, the problem associated with applying an arbitrary word-wrap to output is still on the table, but mitigated by the fact that both the rules and the game board for assume a 2D space. There must have been something in the air in the 1940’s when Mr. Conway was dreaming this up. Scan line television sets had been commercially available for a only a few years, and a patent for a “Cathode Ray Tube Amusement Device”, a precursor to the first videogame, was issued in 1947. GOL gives the appearance of cohesive objects that update in a way that suggests motion, but they are merely tags that are flipped based on evaluations of the surrounding tags. The updating scans just like an old oscilloscope: infinitely but over and over the same field. This is distinct from Turring's machine or Uslam's automata that run over a conceptually infinite tape or column. This introduces a meaningful notion of a neighborhood, where tags update based on the properties of neighboring cells, not just on the history of the simulation. Also of note, is the fact that motion can move "upstream" (kind of), during successive refreshes, although the tendency for glider guns to move down and to the right can be considered an artifact of the scanning.

Casti mentions Schelling’s research from 1971, but even as recently as 1996 a serious study by Epstein and Axtell, affiliated with the Santa Fe Institute, used a variation on GOL to test models of social behavior. Models of social phenomena have actually become much more sophisticated. The Sugarscape model, a customization of GOL represents an individualistic polemic underscored by a Brookings Institution imprint. This is not to say that GOL is wrong, just that it isn't great for modeling society unless you believe that simple rules governing individual behavior give rise larger social phenomena, but do not feed back to the level of the individual...

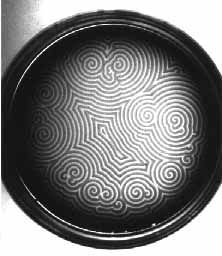

above: a simulation from Epstein & Axtell's Sugarscape

See: Growing Artificial Societies: Social Science from the Bottom Up

http://books.google.com/books?id=8sXENe8QrmYC&dq=growing+artificial+societies&pg=PP1&ots=HLDOY56HRF&sig=3ECV5_fN9JDaHq1Pti__frNtP94&hl=en

R. Keith Sawyer’s Social Emergence does a fantastic job of surveying the research done in this field so far and situating this within classic problems of sociology.

http://books.google.com/books?id=Hgs007Rd_moC&printsec=frontcover&dq=Social+Emergence&ei=VqrDR_j4BYjcygS-gKGsCA&sig=n71iYvGiMj03Di9JonkOKzRboEk

erratum #2: What’s that in Mr. Wolfram’s pocket?

I thought that the shell question related to Steven’s discussion of allometric scaling of seashells in NKS, but realized the shell he keeps in his pocket is probably a tapestry coneshell, a species that happens to have CA-like patterning on it.

This is not B.S. There are plenty of real-life phenomena that behave just like CA.

Above is a chemical reaction in a petri dish known as the Belousov-Zhabotinsky reaction.

No comments:

Post a Comment